The Suvarov atoll (or Suwarov for the New Zealanders and the Cook Islands’ government) is situated nearly 800 miles south of the equator, over 500 miles north-west of Rarotonga (the archipelago's main island), and over 200 miles from the nearest inhabited island, Maithili. Needless to say, you might not find Suvarov in your atlas at home... A shame. Because Suvarov is an exceptional natural site, lost in the middle of the Pacific Ocean (13°14’S, 163°06’W) and is only accessible in a private yacht. The atoll, which measures around 19 km by 13, is uninhabited, but two caretakers sent by the Cook Islands government stay there for 6 months of the year, from May through the end of October. Since 1978, shortly after the death of Tom Neale in Raratonga, Suvarov atoll has become a National Park. Marine life there is very dense, and seabirds live there in their thousands. A Mecca for biodiversity. The atoll takes its name (slightly altered) from the Russian ship Suvorov, in which it was discovered in 1814. During the Second World War, the American writer Robert Dean Frisbie stayed with a few coastguards on Anchorage Island, the main island, situated close to the entry pass to the lagoon. In 1944, Frisbie, who had also lived on the PukaPuka atoll, wrote a book, The Island of Desire, which told of his experience of life on the atolls of this region of the Pacific. Reading this book, and his meeting with Robert Dean Frisbie at Rarotonga just after the war, finally persuaded Tom Neale to realize the dream which was most dear to him: to go and live alone on Suvarov. In 1942, a powerful hurricane devastated Suvarov. The coastguards were sent home to Rarotonga. They abandoned their cabin on Anchorage, along with some makeshift furniture, some water tanks, and a few pigs and hens, which returned to their wild state. The hens which live in freedom on the lost atolls of the Pacific have seen their morphology evolve sufficiently for them to be able to fly again, in a surprising manner. The pigs fed on coconuts, young shoots and berries.

Tom Neale moved onto Suvarov for the first time in October 1952. He was then 50 years old. He stayed there until June 1954, then returned to Rarotonga for a first time, ill. He was only able to return to Suvarov for his second stay in April 1960, until December 1963. It’s these two first stays in the atoll, the most difficult ones, which Neale relates in his book. A third stay took him back to Suvarov in 1966, for around three years. The fourth and final stay was the longest: Neale probably didn’t leave his atoll between June 1969 and his last departure for Rarotonga, in March 1977. The last words he wrote, to stick on the door of his cabin in Anchorage, were dated 11th March 1977. Rarotonga, where Suvarov’s hermit died on 27th November 1977 at the age of 75, victim of a cancer... Which just goes to show that living on an atoll, in the fresh air, and in a very natural way is no guarantee of not catching one of the nasty diseases which decimate the human species.

‘Le corail croît, le palmier pousse, mais l’homme s’en va (The coral grows, the coconut tree grows, but man goes away) – so says a Tahitian proverb, quoted by Tom Neale, who thus lived for a total of around 16 years at Anchorage. Today, Suvarov atoll offers just one authorized anchorage for passing boats, the one situated immediately west of Anchorage Island. We are no longer allowed to go and seek shelter close to Seven Islands, in the south-east of the atoll. National Park requirements. A shame. But understandable. The anchorage at Anchorage is only good when the winds blow from the north to the east-south-east. In all other cases, it quickly becomes unbearable, as the lagoon’s fetch is considerable.

Jangada’s crew with Apii and James, Suvarov’s rangers at the time of our stopover.

On the morning of August 29th, I got the American weather forecast for the Central Pacific. It guaranteed at least 5 days of easterly wind, which favored a peaceful anchorage in the lee of Anchorage. The failing wind had me thinking it was time we arrived, 4 days after our departure from Mopelia. During the night, a curtain of rain squalls complicated the landfall at Suvarov. I preferred to furl the sails, and just keep a tiny bit of jib flying, to continue sailing at 2 knots under autopilot and wait for daylight. Electronic navigation is all well and good, but landing on the reef in the middle of the breakers with my little family would probably not be one of my best cruising memories... Suvarov’s atoll is above all a coral ring, for the most part submerged, with just a few small islands placed on it. As we expected, we only saw the tops of the coconut trees on Seven Islands, then Anchorage at a distance of 6 miles. Suvarov’s wide pass didn’t present any particular difficulties. On our right, I discovered Pylades Bay, a small indentation in the east coast of Anchorage, where Tom Neale used to come to swim. We sailed along the edge of North-East Reef, skirted South Reef where the seas were breaking, and reached the anchorage in the lee of Anchorage. Tom Neale’s little jetty was there, damaged by the southern summer's storms. The Cook Islands flag was flying at the shore end of the little jetty, on the wonderful beach where Neale liked to watch the sun set over the rocks of the reef 5 or 6 miles to the west, while sipping his tea. The little shelter covered in palm leaves that he built for this purpose is still there. It has been maintained by the rangers who succeeded him, and who sometimes used it for their siesta in the shade of Anchorage’s wonderful coconut trees.

We dropped anchor as far north as possible, to take advantage of the best protection from the south-easterly winds. At that moment, I realized another of my cruising dreams. I had wanted to stop over at Suvarov, and we were there! We had only just anchored, when 5 or 6 blacktip reef sharks started circling round the boat.

The two rangers, James and Apii, taught us that we mustn’t throw anything in the water (fish scraps, fruit and vegetable peelings...) in the anchorage area, to try and encourage the sharks to remain in the pass, rather than coming to loiter in the anchorage. A salutary precaution. A small dumping area has thus been defined to windward of Anchorage. You have to take the path leading to the rangers’ cabin at Pylades Bay. Here the sharks know that from time to time, fish are gutted, lobsters shelled, and crab carcasses abandoned. Dorsal fins abound on the surface of the water here, and it’s best not to go swimming. The rangers have put up an explicit sign on the trunk of a coconut tree: "DANGER: Sharks!!! Don’t swim!"

Suvarov is a sanctuary for thousands of birds. Gannets, noddys, frigates, terns, tropicbirds. Very close to Tom Neale’s beach, on Anchorage itself in the northern part, hundreds of noddys nest. From time to time a curlew flies from the reef, calling in its characteristic way.

Tom Neale had a dream. A commemorative plaque reminds us that he lived on Suvarov. Of Tom Neale’s cabin, there remain just a few open work planks, visible in the lean-to which still shelters the little radio transmission room used by the rangers to communicate with Rarotonga. As Anchorage is only inhabited for 6 months of the year, the tropical vegetation has taken over the garden and Tom Neale’s crops once again. The breadfruit trees have aged, but are still there. In 2001, the Cook Islands government built a two-story fare in wood, for the rangers. It’s rustic, but convivial. The water tanks (collected by the roof guttering) are sufficient, and the well dug by Tom Neale through the slab of dead coral in the center of Anchorage is never lacking in fresh water. Blue-water cruising boats can even do their washing there. James Mataa and Apii Williams, the two rangers present when we visited Anchorage, are Maori islanders, with a build close to that of a sumo. They were extremely friendly, and did everything possible to ensure that sailors visiting Suvarov atoll take away unforgettable memories, while not taking their eyes off their mission. James was a carpenter on the island of Palmerston; Apii came from a family of divers and pearl farmers on Manihiki, the island closest to Suvarov, 213 miles away.

You must never give up your dreams, don’t you think?

Happy Tom Neale

With Barbara, we walked round Anchorage via the reef, at low tide. The tidal range is from 80cm to 1 meter. The vegetation on the island is dense, and it is hard to penetrate the interior, with the exception of the camp area. Apii, the assistant ranger, gave us a huge smile. He had undertaken to teach Marin to open coconuts using the islanders’ method. Simple and effective. Separating the coconut from its fibrous outer shell is far from easy. On the motus in the Pacific atolls, a bush grows whose wood is very hard: the miki-miki. Next to each fare on the islands, a miki-miki branch, sharpened to a point, is firmly fixed in the ground. Apii taught Marin, nut after nut, the islanders’ traditional method of freeing the nuts from their fibrous outer shell. He quickly saw that Marin was left-handed, and adapted his movements to our new teenager. Apii also taught us to break the nut into two equal hemispheres, with the aid of a small machete. But his rapidity remained unequalled. I then asked him to show me some uto. The uto, which Tom Neale used a lot to feed himself as well as his hens, is the spongy material which the nut contains at the moment of its germination. The coconut water in the dry nut turns it progressively (until it disappears completely) into a soft nut which sprouts and gives the first green shoots of a new coconut tree. Apii showed us how to make uto fritters: eliminate the upper part of the spongy nut, cut it into fine slices, add some sugar and flour, fry in a little oil. Delicious! Next to the miki-miki wood fixed in the ground, there is always a little wooden stool, carved out of a trunk, on which a metal grater is fixed with coconut fiber ties: the white flesh of the ripe nut is always used grated, and the coconut milk used for example for the raw fish, the coconut cake, and many other Pacific island recipes is obtained by simply pressing these grated fibers in a cloth.

Tom Neale’s cabin at Suvarov.

Hunting, fishing, nature and traditions…

For a few days, James and Apii, the two rangers who were taking their job of organizing life on Anchorage Island very seriously, had been talking about a lobster hunt on the reef... Here we were in the Cook Islands National Park, where ecological fundamentalism, often questionable as it deals with contradictory extremes, is still unknown.

James and Apii are content to practice the ‘fallow land’ principle on the part of the atoll situated less than 5 miles from Anchorage, knowing that in any case, 4/5 of it, further from Anchorage, remain untouched. At the end of the afternoon, a few fish speared in the lagoon were grilled in a wrap on the coconut husk fire, close to the rangers’ faré. We were building up our strength. Apii, who has lived in the atolls all his life, explained to us how the hunt would take place. Departure from Anchorage at around 5.30pm, 1 hour before nightfall, with two boats. The one belonging to the rangers, a small aluminum boat with a 25hp Enduro and a little emergency motor, and the fairly big dinghy from an American ketch in the anchorage. We split up into two groups, which were dropped off around 2 miles either side of Brushwood Island. We would meet up on Brushwood, from where we would return to Anchorage at about 11pm, after spending some 4 to 5 hours on the reef with our feet in the water. At night. Marin came with me; we equipped ourselves: neoprene bootees, lycra vests and Bermuda shorts, diving gloves, head torch with spare batteries, tuna hook, speargun arrow, and a big shopping bag for the lobsters! And off we went for our night-time adventure on the reef! We were with Apii, who disembarked the other little group on Whale Islet. He took us in the opposite direction, to the west, a long way away on the reef, dropped us off, then left. At first we had water up to our waists, and the reef was very uneven, with some big holes! We floundered about a bit, sunset was close, and we felt a little as if we had been shipwrecked on the coral! I thought of the song by Graeme Allwright “In 1942, ...” But Apii knew what he was doing. I had to reassure Marin, who was anticipating a hard time. But this time, I was hardly any wiser than he was, and my son, used to decoding the information coming from his father, knew it... We reached the shallower, less rugged area of the reef, which also had fewer traps for us to fall into. Things got better. We heaved ourselves onto a big coral rock placed curiously on the reef, probably by a hurricane, to wait for nightfall. We could hardly see the anchorage over at Anchorage Island. It was a strange feeling to find ourselves there, out on the reef, at night. But this wasn’t the first time that Franck had come hunting lobsters; he got out a bottle of punch, in which several vanilla pods were macerating. Absolute class. Unhoped-for! We were on Suvarov’s reef, in the middle of the Pacific, and our boat was miles away. The tide was rising, and night was falling. Marin swallowed a mouthful of punch. The stress of the shipwreck disappeared in the fumes from the rum...

To fish for lobsters with a head torch, you have to go onto the reef at low tide, preferably at the beginning of the night, with a bit of moon, but not too much, and a light breeze. At nightfall, the spiny and slipper lobsters leave their hiding places on the outside edge of the coral barrier, and venture onto the reef, towards the interior of the lagoon, to frolic and feed. The technique is simple: you walk progressively along the reef towards the junction with the other team, while collecting a maximum number of delicious animals, but only the adult ones. James was very clear about this. We moved slowly forward, sweeping the reef with our torches. We discovered the whole of the reef’s nocturnal life under our feet. We were walking in 10 to 40 cm of water. Little blacktip sharks, surprised, fled in a panic, grey moray eels slid under the rocks, crabs slipped away quickly. The parrot fish were blinded by the light and froze once they were caught in the torch’s beam. All the glistening colors of the coral passed before our eyes. And from time to time, in a water-filled hole, 2 little orange eyes appeared to anyone who had a good eye: a lobster! Hypnotized by the light, the animal hardly moves at all. However it defends itself, searches for a crack in the rock, and hangs on with all its strength. You have to be positive and determined, using a (gloved) hand and your arm. Marin and I were lucky enough to come across the best spot of the evening: in a water-filled hole, 2 meters in diameter and 50 cm deep, 4 pairs of orange eyes suddenly shone in the beam of our torches! 4 big, plump lobsters! They were superb animals. Guaranteed organic. We also caught a few smaller green lobsters and two or three slipper lobsters. But in the dark, it was hard to know where we were on the reef. There were no longer any landmarks around us. Marin was starting to find that time was dragging; anxiety was progressively setting in. The tide was starting to rise again, so we set off in the rough direction of the little lights we could see in the distance. From time to time, we glimpsed some little sharks, and some grey reef moray eels which fled the light beam. Marin didn’t leave my side, we stuck together. We had to make our way along the reef by guesswork, go round some big water-filled holes, and watch where we were putting our feet. Some seabirds were chattering in the blackness above us – a good sign, we were probably approaching Brushwood. Three quarters of an hour later, we joined the other team, where they were speaking with a strong American accent. Suvarov is on the way to American Samoa from Bora-Bora, and several boats registered in San Francisco, Los Angeles or Salt Lake City were in the anchorage at Suvarov. They had only caught 2 or 3 lobsters, as well as a few eels and big parrot fish. As for us, we had a dozen! We returned to the two boats, then headed back to the anchorage at Anchorage. It was nearly midnight. Barbara and Adelie had left dinner on the cockpit table for us, to be heated up, and some banana cake, before they went to their cabins. Marin and I exchanged impressions. We both guessed that here we had experienced a few hours which would remain fixed in our memories for a long time. We were exhausted, and collapsed into our bunks. Our heads still full of orange eyes. Little blacktip sharks swam between our legs... Good night, son.

Our stay in Suvarov finished with an exciting crab hunt on Turtle Island. Apii took us to Brushwood, then we reached One Tree Island and finally Turtle Island on foot, at low tide. Apii had brought his machete, and some big hessian bags. He was optimistic: it had rained a lot in the last few hours, which encourages the crabs to come out of their holes. They usually prefer the darkness of the night to venture onto the motu. The caveu is the big coconut tree crab, which as an adult can weigh 4 to 5 kg. It has extremely powerful pincers, capable of cutting off a human wrist, so they say. The caveu has a speciality: opening coconuts, a very physical exercise. Naturally I am talking about the husk, as the nut itself is just too easy! But the caveu is slow, Apii reassures us. The sturdy ranger, accustomed to life in the atolls, nevertheless asked us to count our fingers before and after the hunt, with a little smile at the corner of his mouth... He explained to us how to spot the caveu, how to catch it, and how to kill it before putting it in the bag. With his machete, he opened up a little path through the dense, wild vegetation of Turtle Island. We swept along behind him. Neoprene gloves, sticks, sandals. A few minutes later, a first caveu was spotted. It tried to hide itself in the inextricable jumble of the roots of a bush, and Apii had to use all his experience. The combat lasted a few minutes, as the animal didn’t want to end up in the promised saucepan. But Apii is a mountain of muscle and his hands aren’t delicate! We discovered what a caveu looks like – closer to the configuration of a hermit crab which has lost its adopted shell than a crab from the rocks of Molène, back home. A nice-looking animal, bright blue, but sometimes also with an orange tinge, depending on its eating habits. It has a pouch at the back filled with an oil that is fragrant with the aroma of coconut, and which by dripping onto the animal when it is cooked on a wood fire, gives it a creaminess full of flavor close to that of foie gras... To get hold of it without danger, you must grasp its two pincers and its two biggest legs in the same hand, and it can then no longer harm you. You must therefore catch it with a brisk, determined movement, which not everyone likes doing... It was Barbara who found the best spot: two big caveu together, chatting about the night’s rain. I caught them and killed them one after the other, as if I had been doing it all my life. The crab’s death is sudden: hold it firmly by its 4 main appendages, place it on a firm support, grab its shell at the bottom of its face (if we can call it that), and turn it suddenly through 180°, with a vigorous lethal rotation movement... A sinister cracking can be heard and according to my modest neurological knowledge, I believe that the animal’s nervous system is seriously affected. The maneuver is irreversible. One more for the bag. We only hunted the very big crabs; we were in the Cook Islands National Park after all!

Apii decided to teach Marin to use the branch of a miki-miki to open the husk of a coconut. The best school in the world!

The evening before our departure, the communal dinner in the rangers’ fare was grandiose: as much lobster and crab as we could eat!

Wonderfully prepared by James and Apii, who also made some uto fritters. James, who is the cook at Suvarov, said a few words of welcome to each of us, Apii said a prayer, first in English, then in his Cook Island dialect. With his eyes closed, he thanked God for his life at Suvarov, the encounters with passing crews, yesterday evening’s lobster fishing, and the presence of each of us around the table, in the open air under the awning of the faré. Suvarov will remain a brilliant memory of the Pacific for the four of us. The next day, we left for Rose Island...

The caveu can have different colors, but the same delicious flavor!

Before going back to sea to head west, a huge helping of crabs and lobsters from Suvarov!

Jangada – le livre

Retrouvez les aventures de Jangada dans le livre Voyage autour du monde (en deux tomes), disponible dans notre boutique Internet. Un ouvrage indispensable pour tous ceux qui envisagent de partir en voyage en bateau et pour tous les amateurs de bonne littérature !

A commander sur www.multicoques-mag.com

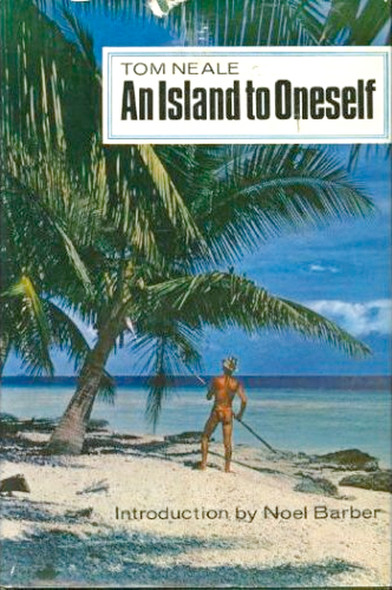

Tom Neale’s book ‘An Island to Oneself’. A cult book. A must-read.

Vote for your favorite multihulls!

Vote for your favorite multihulls!

What readers think

Post a comment

No comments to show.