Brisbane / Darwin - Cruising Tropical Australia (2/2)

Destination - PacificIn Multihulls World #176, our Australian correspondent Kevin Green explored the first part of the route from Sydney to Brisbane. We’re setting sail again with him as he continues his voyage northwards. On the itinerary, the Tropic of Capricorn, warm waters, and the Great Barrier Reef!

|

|

At 170 nautical miles north of Cairns, Lizard Island has a world class resort and a popular anchorage with supply barge from the mainland.

The Whitsunday Islands are a serene cruising region and host Australia’s most prestigious regatta – Hamilton Island Race Week – in late August.

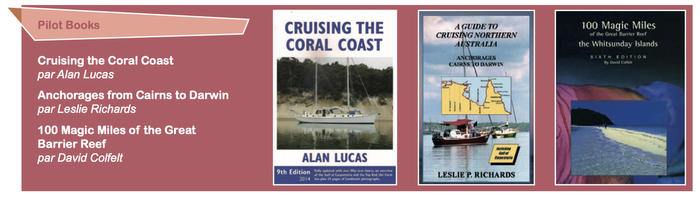

The major city of Brisbane in the northeast of Australia is a good place to prepare for your voyage around the tropical part of this vast island, one of the remotest sailing regions in the world. Ideally done in two parts: the east coast and then the north coast. Called the ‘Top End’ this northern coastline stretches for 1,000 miles between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean. The voyage will take you between the only two cities in a region half the size of Europe, yet sparsely populated and teeming with wildlife, including many that want to eat you. This voyage has to be done in the Australian winter (April through September) to avoid the cyclone season and to use the prevailing southerly then easterly winds. Brisbane’s international airport makes it an ideal place for crew changes, perhaps for those leaving who have done the first leg from Sydney. Beyond Brisbane, and the sheltered Moreton Bay that is a tranquil departure point, are hundreds of islands and the Great Barrier Reef in what is undoubtedly one of the world’s pristine cruising grounds. Paper charts and the cruising guide books should have been thoroughly read, both for safety and to help you explore. Given the amount of coral ahead, loading several spare anchors and rode is advisable, remembering that it’s often too dangerous to dive because of sharks and crocodiles.

The first leg of this voyage is along the Sunshine Coast region of long beaches and big surf on the Great Sandy National Park. About 45 miles north is the major “multihull friendly” marina and town of Mooloolaba which is a popular port to explore the region. Beyond, another day’s sail is the largest sandbar island in the world, Fraser Island with an inside passage guarded by the infamous Wide Bay Bar. Weeks can be spent here, exploring the national parks and shoreside facilities including restaurants and yacht clubs.

Making a northerly course, our Seawind 1250 approaches Lizard Island

Sailing to the reefs

Beyond the Fraser Coast requires good navigation because of the many coral reefs, which can be anchored among if the weather forecast is mild. Major towns with large marinas are here, such as Bundaberg, home of Australia’s most famous rum distillery. The coast is a myriad of channels and islands such as Curtis Island and Keppel Bay that are popular cruising destinations. However, for those blue water voyagers, it is the world-famous Whitsunday Islands that will pull you over the horizon to this chain known as the ‘100 magic miles’ and includes the prestigious Hamilton Island where the annual sailing regatta takes place late August. The mainland town of Airlie beach offers cyclone shelter... and supermarkets.

Departing Airlie Beach in August one year, I recall thinking “Wow, we have to sail 3,000nm with little human contact until the city of Darwin!”. Our island-hopping route would take our catamaran, a Seawind 1250, through the myriad channels of the Great Barrier Reef calling at some of the interesting islands and bays made famous by the early explorers including Cook, Torres and past the treacherous Bligh Passage. French exploration mainly focused on the SW of Australia, and of the half dozen major expeditions, Nicholas Baudain’s in 1800 was the most successful. His legacy is still much in evidence, with places and even animals bearing his name.

Moored at Hinchinbrook Island, where we entered crocodile territory. Crocodiles are the deadliest predator in tropical Australia – one or two deaths a year. Amphibious, they are capable of land speeds of 20 mph in short bursts.

Magnetic Island

With the 6am sunrise after a clear starry night’s sail and little shipping to dodge, the peak of Magnetic Island appeared on the horizon like an upturned ice cream cone. As the strengthening springtime sun warmed Horseshoe Bay, we anchored on clear sand before dinghying ashore to the small strip of shops for refreshments. On past visits I’d wandered along the wild nature trails, encountering spiky echidna’s, startled rock wallabies and luxuriated alone among secluded sandy coves. Our few hours ashore and swim in wa- ters of 25°C (77°F) was lovely, safe from the deadly jelly fish that are summer visitors only. After another night sail, daybreak revealed Hinchinbrook Island’s jungle-clad mountains, with no sign of human habitation except for a big sign on the beach warning of the presence of saltwater crocodiles. The ‘salties’ are one of our deadliest predators being amphibious (with land speeds of about 20mph) and having torpedo like underwater prowess; and humans are a favorite prey. I’ve also seen them jump several meters in the air. Later that afternoon we sailed northeast for a snorkel on the inner Great Barrier Reef, weaving our way slowly among the tall coral heads, or ‘bommies’ as they are known, before anchoring. I finned for an hour among the brain and stag corals, encountering colorful clown fish, parrot fish and majestic rays. Then, wanting to take advantage of the strengthening afternoon breeze we sped north for the 70nm overnight run to Fitzroy Island followed by a short hop to the Great Barrier Reef town of Cairns, the most northerly city on the east coast.

James Cook climbed to the summit of Lizard Island in 1770, in the hope of sighting a passage to get his ship back to sea.

In the wake of Captain James Cook

Dodging the armadas of backpacker boats blasting out pulsating beats at Cairns, we steered north to clear horizons. The 20-knot winds caused us to put one reef in the fully battened mainsail as we sped off at nearly 10 knots for the 170nm leg to one of the few places where Captain Cook came ashore during his 1770 voyage, Lizard Island. As night fell, only a few lights twinkled in Cooktown, the small hamlet where Cook beached HMS Endeavour after his near fatal collision with the Reef. At this latitude, the coral edges towards the coast, so good navigation is critical. Unlike Cook, who had to rely on a sextant and a version of the John Harrison’s famous clock for longitude, we used waypoints on the chartplotter, skirting the edges of the inner reef as we snaked our way north in the narrowing channel. Surprisingly, large vessels use these passages, so my night watches for the following days occasionally included dodging ore carrying cargo boats and prawn trawlers. Reaching Lizard Island the following day, we passed its beautiful Blue Lagoon that glistened in the late afternoon sun. Lizard is a popular anchorage for east coast cruisers and had 17 other yachts anchored. Cook came here in the same month in 1770 and was unhappy, having just spent months repairing the Endeavour and was keen to find a way out of this “infernal reef”, so he spent the afternoon climbing the 1,178-foot (359m) peak to what has been named Cooks Look. His reward, like ours, after the two-hour climb through dense bush and rock, was a vista north of coral reef as far as the eye could see. To the east beyond a sandbar islet lay yet more pale blue sea, signifying coral; but there were some dark blue gaps. It was here – Cook Passage - that he escaped to the Coral Sea. We would not be following him, as the inshore route was the quickest for our course around the most northerly point of Australia: the slender landmass of Cape York that takes sailors just 70 miles south of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

|

|

Here at Cape York, Australia’s closest point to the equator (10° 41’ S 142° 31’ E). Mission accomplished for skipper Royce(L) and first mate, author of this article!

Using the night-sight helped Kevin entering anchorages... and spotting crocs.

Shark Attack

In the dawn of yet another clear morning we skirted along a chain of sandbar islands seeking a sheltered anchorage for some snorkeling and chose the imaginatively name Sandbar No.8 National Park Island, a coral strewn mass of scant vegetation and pristine beaches. Walking around the edges to avoid disturbing the birds we watched the acrobatics of boobys and terns. But our swimming was spoiled by the sudden appearance of large tiger shark that chased my crewmate into the shallow coral. Seeing the danger, I rescued him in the dinghy, and we all breathed a sigh of relief. Back out at sea with all limbs intact, we were on the final leg of our east coast part of the voyage before our westerly turn. We threaded our way through the inside channel of the Torres Strait at Endeavour Strait on a fast-moving tide towards the low-lying Cape York, skirting past palm fringed coves and a solitary hamlet, before anchoring on sand just beyond the Cape. Ashore we met exhausted off-road drivers who’d made the 1,000km (620 mi) pilgrimage to Australia’s most northerly point. Our final run ashore in the region would be the nearby Horne and Thursday Islands before the three-day crossing of the Gulf of Carpentaria. At Horne we wandered among the aboriginal community and walked the dusty main street to the hotel for a bar meal of fresh Barramundi fish and ice-cold beers. The beer garden had a six-foot steel mesh fence to prevent the crocodiles from eating the guests, so we relaxed with some extra beers.

Making passage west, lonely Booby Island was our last landmark before our 300nm crossing of the Gulf of Carpentaria. During the three-day voyage only a few south-going ships were encountered while the days remained sunny and sufficiently windy to keep us moving. At night a full moon dominated the starry sky, and I used the iPad Sky View app to identify all the stars and even satellites. So, keeping our course parallel to the Southern Cross constellation, we edged our way west, passing through acres of orange coral spawn, activated by the full moon. Landing fish on our two trailing lines was exciting with a 35 lb (16kg) Spanish Mackerel being our largest.

A happy crew having landed a 35 lb (16kg) Spanish mackerel on a towed lure; we also landed some bluefin tuna as well.

Northern Territory

We dropped the hook in to the sheltered Gove Bay, dominated by its huge bauxite processing plant, but also home to the recently reopened Gove Yacht Club. Departing, the anchorage we weaved our way back to sea through the dozens of long- term cruising boats that had wintered here but would probably be heading east as the October wet season arrived. The last leg of our voyage to Darwin would be mostly offshore in the Arafura Sea once we’d threaded our way through the shallow Gugari Rip, between the Wessel Islands, a 500m ‘hole in the wall’ shortcut where the tide flows strongly. Onshore the rough bush and sandstone sides lit up with the bright sun while dark haired rock wallabies ran for cover under pandanus palm trees, a very tropical scene which must have astounded the early explorers. This pristine wilderness is aboriginal controlled land, so no hunting is permitted, and the low-lying islands are a haven for marine life. After anchoring, we glided in our dinghy across crystal clear waters among mangroves, where small crocodiles slid past while further up the creek baby sharks sunbathed among the sandy shallows. Elsewhere, large shadows moved below us in the deeper parts of the bay as 6-foot (2 m) manta rays glided sedately past.

Sailing west for two tranquil days with light winds brought us to our last major obstacle before Darwin, the Coburg Peninsula and Port Essington, where the early British settlers had attempted to establish a township. After anchoring and going out in the dinghy I had reached for our only weapon, a small axe, as a crocodile much larger than us approached, but thankfully, swam by without attacking. Another two days of enjoyable sailing followed, as our catamaran effortlessly slid along in the light tropical airs to reach Darwin. Nearing the populous center of some 130,000 inhabitants, we could smell the spicy mix of city life and see its faint glow, yet still only a mere dot of light on this wild coast...

Dawn arrival in Darwin, the only major habitation on the lonely northern coast of Australia. The nearly 26-foot (8m) tidal range requires marinas to have lock gates, but the welcome is friendly, especially at the convivial yacht club.

Destinations offered by

View all the destinations

Subscribe and get 8 issues a yearfor just $39.90

subscribeClassified ads

View classified adsSABA 50 Maestro 5 cab (YM 2016)

- Location :

- Port St Louis du Rhône, France

- Year :

- 2015

Discover the 2026 boats!

Discover the 2026 boats!

What readers think

Post a comment

No comments to show.