Issue #: 203

Published: October / November 2025

- Price per issue - digital : 6.50€Digital magazine

- Price per issue - print : 9.50€Print magazine

- Access to Multihulls World digital archives Digital archives

Our senior sailing reporter Brieuc Maisonneuve took advantage of a delivery trip (part of which he completed single-handed) at the helm of a trimaran to take stock of what is involved in preparing for solo sailing.

Some offers are too good to miss! I’ve got a couple of friends who own a Neel 43, and they asked me to deliver their trimaran from Carteret, in Normandy, to Venice, Italy. The plan was a superb 2,000-nautical-mile voyage with a few tricky areas to navigate: getting clear of the Western Approaches (to the English Channel), with their strong tidal currents and heavy maritime traffic, the crossing of the Bay of Biscay, the descent southward along the Iberian coast with the potential risk of encountering killer whales, the passage through the Straits of Gibraltar, then across the Mediterranean and the Adriatic, two seas with often-changing conditions.

The good news is that the multihull had to be in port by July 1 at the latest. By planning to leave in mid-May, I could choose the right weather window.

To keep my skills sharp, I decided to sail solo for the first leg to Porto. A crewmate would then join me to continue the voyage. In this article, I invite you to join me in preparing for the trip. Later, in a second article, we’ll have a look at how it progressed!

Before casting off, there are several essential aspects to check:

- Safety equipment

- Technical preparation

- Provisioning

- Weather and sailing strategy

Having summarized all this information, I compile it into a “route plan.” This document is essential, regardless of the length of the voyage, and is even mandatory for insurance purposes.

In addition to the regulatory equipment for a Category A boat, I pay particular attention to the safety of the sailor, in this case... me! The goal is to avoid falling overboard at all costs. With a crew, it’s already critical, but single-handed it’s the only option. So, I prepared a 150 N auto-inflating life jacket with an MOB-AIS beacon, which is automatically activated in the event of falling overboard. This device uses AIS technology to transmit an immediate alarm to all vessels equipped with an AIS receiver within range (usually 5 to 6 miles). The aim is to enable rapid, localized, and effective recovery by nearby vessels.

In addition, I also carry a PLB (Personal Locator Beacon), an individual distress beacon that functions like a mini EPIRB. It transmits an alert via the 406 MHz frequency to the international GMDSS network (Cospas-Sarsat), which then relays the information to maritime rescue centers. However, unlike the MOB-AIS, the PLB does not transmit locally, and it can take up to thirty minutes for the alert to be processed before a rescue operation is launched.

The two systems are therefore complementary: the MOB-AIS allows for rapid intervention nearby, while the PLB is a reliable means of alerting the Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC).

I also make sure I have a recharge kit available for the life jacket in case of accidental activation (in this case, there were actually six life jackets on board, so I was well covered).

My life jacket is equipped with a lanyard with two carabiners so that I am always clipped on when moving around on the trimaran. I check the load indicators to make sure they have not been tampered with.

Another essential point is to see and be seen, especially at night, because as everyone knows, according to Murphy’s famous law, trouble only happens at night. So you need at least two headlamps: one fixed to your hat, the other within easy reach (I always put mine near the chart table).

I also add a powerful, waterproof flashlight that is quickly accessible, as well as a good supply of spare batteries for all these lights.

Another safety feature for solo sailing, but one that was unfortunately not installed on this multihull, is a remote control for the autopilot. This would have allowed me to change the autopilot while trimming sails, reefing, etc. During the 2014 Route du Rhum, if I hadn’t had my NKE remote control around my neck, I wouldn’t be here to write this!

I put a 30-foot / 10-meter coil of Dyneema and a few sail ties in my bag, just in case.

To finish this random inventory, experience has unfortunately taught me that having a dedicated tracking beacon for the boat is not an unnecessary investment. If, for whatever reason, you have to abandon the boat, this beacon will allow you to locate your boat for up to 30 days, whereas your EPIRB will stop transmitting after 72 hours at best... Personally, since that fateful day on November 13, 2022, I always have a small YellowBrick beacon with me, which I install on board in a place where it can transmit whatever the situation!

The trimaran hadn’t actually sailed since July 2024. I had already gone aboard in the winter to check that the engine and generator were working properly.

However, the hulls were very dirty.

The day before departure, I went down to the boat at low tide to limit the current and spent a good hour in the still very chilly water cleaning the hull, checking the through-hull fittings, the bow thruster, and the propeller. Not having a wetsuit to hand, I used one of the boat’s survival suits. It’s not very practical for diving, but at least I wasn’t cold, and it even created a bit of a stir in the port of Carteret, with onlookers wondering what new species of seal is colonizing the harbor. The result wasn’t perfect, but I knew I could always finish off the hull in the Mediterranean, in slightly warmer waters.

I then checked that the standing rigging was properly adjusted and in good condition, that the genoa and staysail furling systems were working, that the winches were operational and, above all, that the reefing lines were working properly.

There’s nothing worse than wanting to reef at night and discovering a problem: it’s dangerous for both the equipment and the sailor.

I also checked that the gennaker halyard was in place and not twisted, that the winch handles were stowed away, etc. I finished with a complete test of the electronics, the autopilot, and the wind instrument. As I was going to be sailing downwind a lot, I checked that the log was working properly because if it isn’t, you’ve got no true wind data on the displays. When sailing solo, a malfunctioning autopilot or wind instrument is a NO GO!

This is far from a minor detail: food and water are a sailor’s fuel. When single-handing, you have to conserve your energy to stay alert. Falling asleep suddenly due to exhaustion means failing to keep watch.

I favor a healthy diet: protein, fat, a little slow-release sugar - and I avoid fast-release sugars that cause insulin spikes. I choose foods that are easy to cook: eggs, ham, chicken breast, a little greenery...

Fortunately, aboard a well-equipped cruising multihull with a proper galley and a refrigerator, there’s no need for freeze-dried food like you find on ocean races. I just plan a few quick meals for difficult times (bad weather or high alert areas).

As for drinks, water is the answer! Three liters (100 oz) a day is recommended, so I carried two six-packs of 1.5-liter bottles - the watermaker was to take care of the rest. Of course, I set off with a full tank of water, and diesel, too.

I still remember that moment in the 2003 Mini Transat when, on getting clear of the doldrums, I discovered I had 12 liters (just over 3 US gallons) of water left to last me for the final 1,000 nautical miles... Ever since, I prefer to plan for the worst.

I also take coffee, but mainly tea, which is excellent for replenishing calories in cold weather. Sailing solo is serious business, so it’s a dry boat: the beer will have to wait until we stop in Porto.

A week before the planned departure date, I began monitoring the weather situation in the North Atlantic. It was still too early for forecasts that would be reliable, but it allowed me to familiarize myself with the general synoptic picture: the position of the Azores high, the presence of low-pressure systems, and so on.

To do this, I use the UK’s Met Office pressure charts (weather.metoffice.gov.uk/maps-and-charts/surface-pressure) and cross-reference them with the picture from the Windy app, which is very visual and gives a good overview of the situation.

Four days before departure, I started to refine my plans. The European (ECMWF) and American (GFS) forecasting models were beginning to converge, which reduced uncertainty. I scrutinize the wind fields and, above all, the sea conditions.

This was a delivery trip: there was no need to get tossed around. So I set myself some reasonable triggers: no more than 25 knots true upwind, 35 knots downwind, and no seas higher than 3 meters (10 feet).

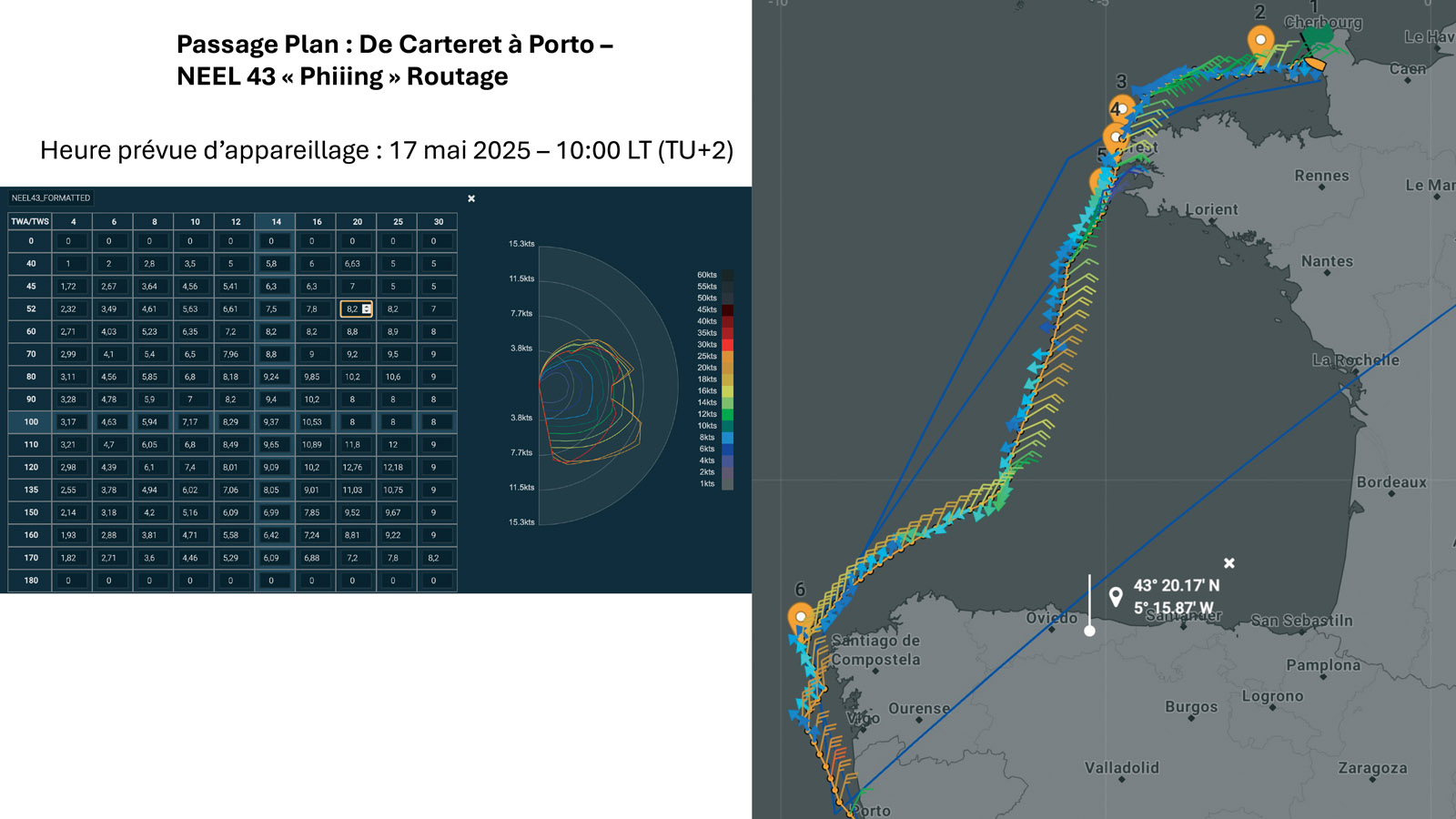

I usually use Adrena software (www.adrena-software.com/en/) for routing. It’s a very powerful tool that allows you to plan complex routes with many variables, perfect for offshore racing. But my laptop was still aboard another boat, in the Bahamas... So I was falling back on Squid X (www.squid-sailing.com/en/), very good online routing software that allows you to build a precise and simple strategy at a low cost. A subscription to get high-resolution files for Europe costs €34 per year.

To perfect your knowledge of weather and planning, I highly recommend reading some of the specialist works on the subject that provide a good understanding of this discipline, which may seem a little tricky at first.

However, I would advise against “asking a friend who is a skipper and knows about these things” if you don’t have the skills to plan your route yourself. Call in the professionals: it’s not very expensive and it will save you disappointment when your “friend you need to call if something dangerous happens” has gone off to play golf and left his cell phone in the car...

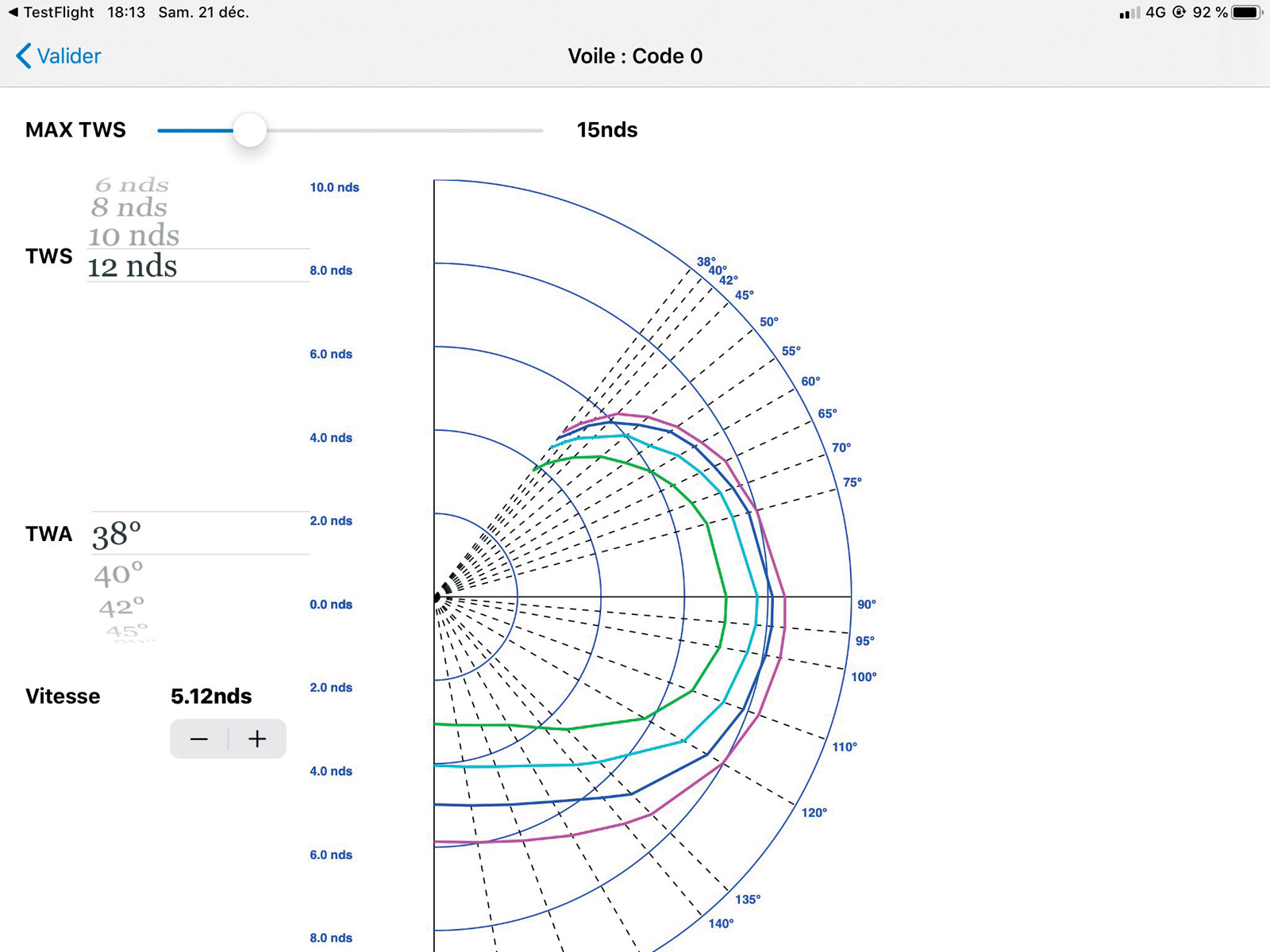

Many owners are reluctant to use routing software because they don’t have accurate speed polars for their boat. In my opinion, this is not a real problem. You don’t need a model that’s accurate to the degree and knot, as you would for an offshore racing multihull.

Hull performance curves are mainly used to plot realistic angles for the multihull and the skipper. When sailing solo, I hardly ever steer, so I have to force the trimaran to sail at angles that are easy for the autopilot to handle.

When sailing close-hauled, I limit myself to a true wind angle (TWA) of 55° so I can maintain good speed without having to constantly bear away and pick up again, especially if sailing in confused seas. When sailing downwind, I set the boat between 140° and 150° TWA under spinnaker, depending on the wind strength.

I set appropriate angles for each point of sail: 80° TWA when reaching under genoa in 15 knots, 120° under spinnaker. I deliberately degrade the polars between 85° and 115° TWA beyond 22 knots, as this is a “gray” zone: should I luff up? Or bear away? Or ease the sheets? These are tricky angles in a breeze for a multihull.

I degrade the polars very sharply from 30 knots of wind to simulate the impact of the sea and avoid the routing sending me systematically into strong winds.

Once all this has been entered into an Excel spreadsheet, I generate a “.pol” file that can be interpreted by any routing software. It’s not perfect, but it’s enough to navigate efficiently and safely, and to plan your route reasonably accurately.

The great advantage of routing is that it structures your navigation with milestones: For this trip, what time would I pass Ushant? When to round Cape Finisterre?

I therefore segmented my route as follows:

- Departure from Carteret and approaching Jersey

- The Western Channel

- Passage of Pointe Bretagne

- Bay of Biscay

- Rounding Cape Finisterre

- Spanish west coast and Portugal

- Arrival in Porto

For each segment, I studied the wind, currents, water depths, sensitive areas, ports of refuge, favorable times for sleeping, etc.

I never navigate by following a route with fixed waypoints, but rather by aiming for wind angles and key positions to approach the next leg in the best conditions.

This makes sailing more active and interesting. Once all the data has been collected, I summarize it in a passage plan. Before setting off, I send it to the relevant MRCC, in this case, France’s CROSS Jobourg (jobourg@mrccfr.eu). This is not mandatory, but it would be a real bonus in terms of safety.

I also gave myself a little leeway by sending an email to the Porto marina to reserve a berth, specifying in my message that I am sailing solo and may need assistance with coming alongside. Ideally, you should know the layout of the marina in advance so you can visualize the maneuvers needed on arrival. In addition to nautical charts, I use Google Earth a lot to see where boats are moored in an estuary or whether the fuel station is a stone jetty or a pontoon.

More and more recreational sailors are adopting symmetrical downwind sails with integrated wings, often used without a mainsail, which is left neatly stowed in its lazy jacks. This concept is appealing because of its simplicity, especially for those who want to avoid dealing with a spinnaker or mainsail adjustments.

Personally, I’m not a fan because this configuration makes sailing very “passive,” and our modern multihulls are fast and light: we get much better VMG by sailing higher and faster than downwind.

From a structural point of view, sailing without a mainsail is not ideal. It is the leech of the mainsail that holds the mast in place: in the long term, this can damage the cars and the track, or even lead to dismasting.

The great advantage of good preparation is that it minimizes any “surprises.” My trip went smoothly. I arrived two hours behind schedule due to a weak front that arrived as I closed Cape Finisterre. The conditions forced me to tack a few times between La Coruña and Cabo Vilano. I then had to motor through a small ridge until the northeast flow reestablished itself. I had a bit of a scare a few hours before arriving in Porto when a large marine mammal started playing around the bow of the trimaran and then came to sniff the rudders. It left after a few minutes as quickly as it had arrived. A few days later, in Barbate, where a Sea Shepherd team is deployed to educate recreational boaters about interactions with orcas, I was able to show photos and a short video of my “beast.” After analysis, it was identified as a False Killer Whale, a fairly rare species that is not aggressive toward boats!

Arriving in Porto was very easy: I went straight to the fuel dock, which was clear. The marina staff gave me a particularly warm welcome, and the small fish restaurants in the nearby village quickly revived a somewhat tired sailor. A stopover I highly recommend!

There are a multitude of ways to prepare for sailing. Personally, my method is a combination of empirical experience gained in offshore racing and more academic learning, as taught in the RYA’s Yachtmaster course. There’s probably no perfect method but sticking to a few automatic routines allows for more serene sailing aboard your multihull.

What readers think

Post a comment

No comments to show.