Issue #: 157

Published: January / February 2018

- Price per issue - digital : 6.50€Digital magazine

- Price per issue - print : 8.90€Print magazine

- Access to Multihulls World digital archives Digital archives

Eventually, you have to get round to leaving the Pacific Ocean. And yet, I would come back, to push my bows a little further, in areas I love which are off the beaten track. On board Jangada, we crossed the Torres Strait with a stiff breeze, a low, dark sky, and mostly at night. Which is not a recommendation for beginners ... I say this modestly, but make no mistake, it can be a dangerous patch.

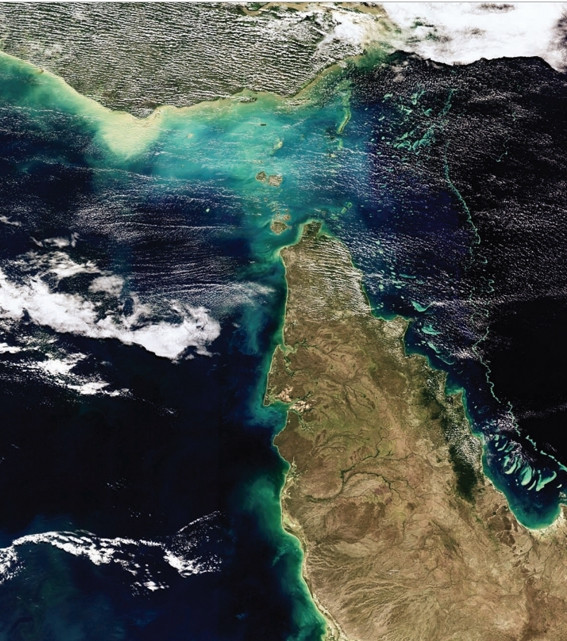

For the moment, more prosaically, we are in what I call elegantly the exit of the Pacific. This region, all the way to the west of that great ocean, forming a funnel between the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea in the north, and Queensland in Australia to the south, has repeatedly shown us in recent weeks that clouds are concentrated here, with winds, thunderstorms and rains. To continue the metaphor, let's say that our sailboat could be temporarily compared to a small pearl in the Pacific which had been inadvertently swallowed by the huge ocean and which then gets spat out again on the way out... at the Torres Strait, and into the Indian Ocean!

Back to the light, the blue sky, the sun of the tropics, on the sea side of Arafura. Our plan now is to move from the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean. To do this, you have to cross a complex marine region in terms of cartography, a region that so preoccupied the great navigators of history that they sometimes had trouble sleeping weeks before they reached the area. We know that one of the reasons that contributed to the mutiny on board the Bounty in Tonga was Captain Bligh's growing nervousness at the approach of the Torres Strait, in the face of what he saw as increasing complacency among the crew on board the ship during the months when they were stopped over in Tahiti. A situation he had difficulty in managing as the crossing of the strait approached, and was the last but also the most serious obstacle to the success of the mission entrusted to him by the British Admiralty.

I, a modest 21st century sailor, using electronic charts, satellite navigation, and sailing aboard an excellent sailboat, can tell you that trying to cross the Torres Strait and its many dangers, at the end of the 18th century, in the state of known cartography and navigational instruments available at the time, with heavy, un-maneuverable sailboats, would have been a high-risk adventure. To succeed in crossing it was a feat. Getting shipwrecked was the norm.

Waiting out a gale in Port Moresby, I spent time studying the area of the Strait. I plotted for this exceptional event on our two GPS, a set of at least twenty waypoints, which mark out the sections of the route we would have to follow in the Strait to reach the Arafura Sea.

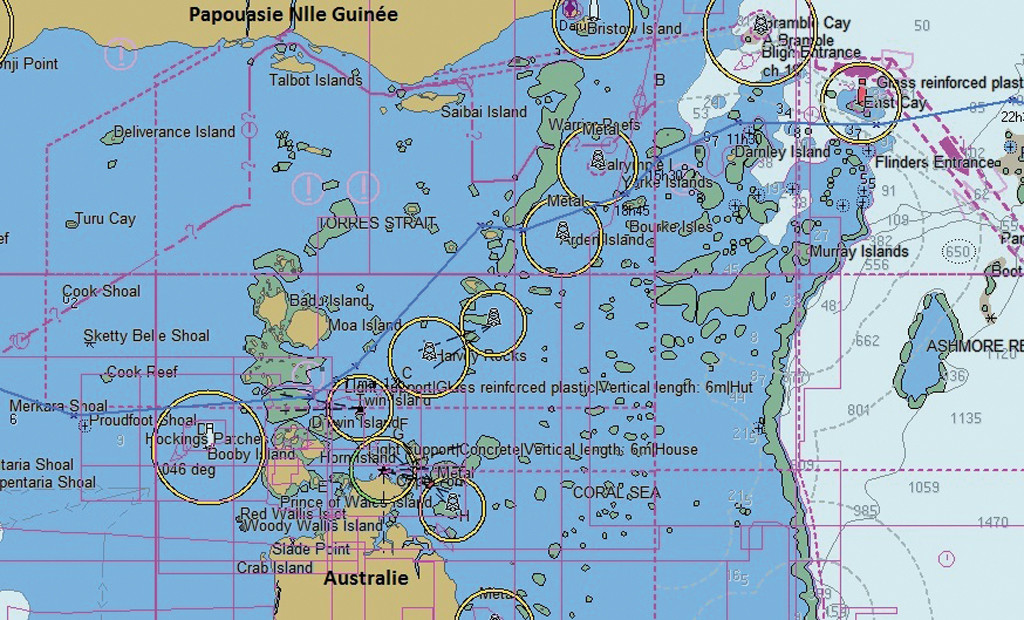

81 nautical miles separate the north-south axis of Cape York, the northernmost point of the Australian mainland, from the southern tip of Papua New Guinea. This complex passage is riddled with shallow shoals, coral reefs, islands and islets set here and there at the whim of the Great Barrier Reef, whose fabulous underwater life extends as far as this. So, along an east / west axis this time, the coral formations occupy an area not less than 180 miles wide, forming an impenetrable barrier to navigation, with the exception, from the east, of two passages close together, a few miles north of Cape York on the Australian side. The waters are shallow, the depths being between 10 and 15 meters, which naturally limits the size of merchant ships that can transit.

Coming from Port Moresby, Jangada will use the Great North East Channel. In contrast, boats from Australia's Queensland take the Great South East Channel, a 400-mile long channel that winds between coral reefs within the Great Barrier Reef to the latitude of the city of Cairns. These two channels meet north of Cape York to continue west as the Prince of Wales Channel, which leads to the open waters of the Arafura Sea after about fifteen miles. To this very particular geography of the place are added two criteria which complicate the situation still further: Firstly, the South-equatorial current of the Pacific Ocean pushes its waters towards the west in the Strait, which creates a main flow heading west; and, on the other hand, the alternating tidal current adds to, or withdraws from, the south-equatorial current. In some places in the Torres Strait there are currents greater than 10 knots, but let’s say that in the useful part of the Strait, currents of 2 to 5 knots are commonplace. The incredible number of reefs that clutter the area still has an advantage: the sea is broken systematically, and the size of the waves is reduced. In manageable weather, we sail in relatively calm waters

June 27th: Depart from Port-Moresby. Wind 25 knots. We head to our first waypoint, around 135 miles to the west. The sky is low, charged with big dark clouds which roll quickly across a gray sea. As always when the navigation is going to be tricky, I have spent ages studying the charts and the weather forecasts. I am confident, almost serene. I have prepared my navigation for this trip, and I have in mind all the useful information, including those relating to a possible fallback solution. On complex passages, there is no question of being surprised. My crew show little enthusiasm for this important departure, but for my part, I’m keen to finish quickly with this dark corner of the Pacific. The first danger to ward off before entering Torres is Portlock Reef, about ten miles south of the route. In such weather, the sea breaks in an absolutely grandiose way... Whether you pass north or south of Portlock Reef, the ocean floor suddenly rises from 1,200 meters to less than 100 meters. These are like steps built on the edge of a great big oceanic swimming pool. I watch with amusement the screen of our sounder as it shows this vertiginous rise. We are still 65 miles from Bramble Cay, which marks the northeastern entrance to the Torres Strait.

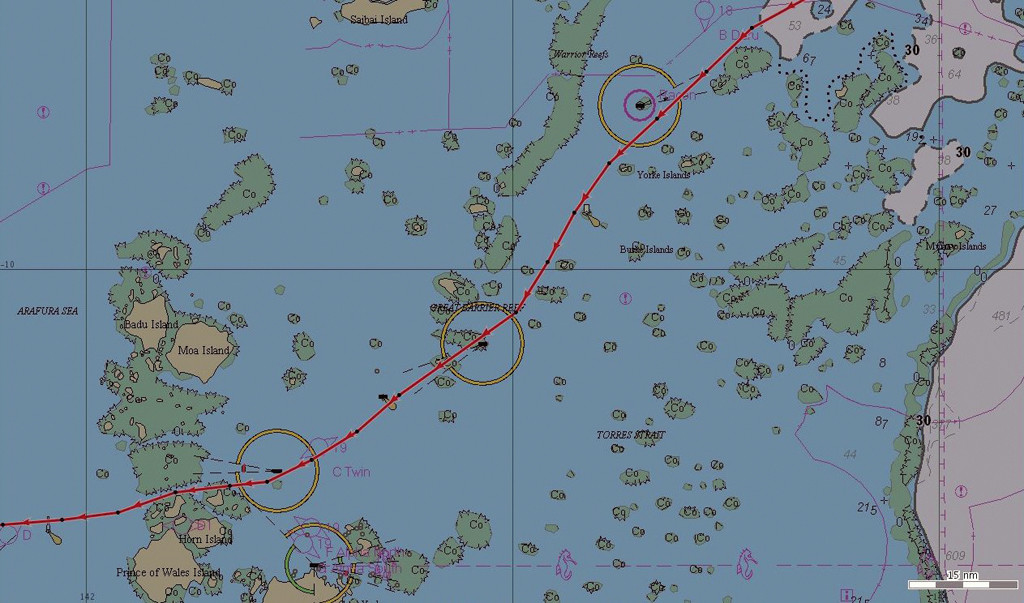

The night was hectic, but we made good progress. Another gray day rose over an equally gray sea. 35 miles further on, we leave East Cay to port. South of this reef is a secondary entrance to the Great North East Channel, Pandora Passage, which leads to Flinders Entrance. From there, the NE / SW crossing of Torres Strait represents a 133 mile straight line route in the midst of the reefs along an average course of 233° between Bramble Cay and the Harrison Rock buoy at the end of the Prince of Wales Channel, before opening into the Arafura Sea.

In reality, crossing the Strait represents exactly 141 nautical miles among shoals. The first segment of the route runs at 236° for 27 miles to Stephens Islet on the port side. The depths are no shallower than about forty meters. The next segment runs at 224° for 29 miles, as far as Arden Islet, to port. To the west lies the immense expanse of Warrior Reefs. In the middle of this segment there is a first possible anchorage to leeward of Dalrymple Island on the starboard side of the channel, usable by those who prefer to avoid sailing at night in this maze of coral formations hemmed in with so much current. Despite the absence of radar (it had been out of order for ages), our choice from the moment that we knew we could rely on the electronic charts, with 2 programmed GPS at the same time at the chart table, and generally-ok weather, we managed to go at a good pace without stopping or taking into account the daylight. But this choice might not necessarily be the best for everyone.

The third segment at 209° for 15 miles meant we had to harden up into the southeast wind more and more, until Dove Islet was abeam starboard. The depths were then less than twenty meters. The next segment was 14 miles at 213°, with a slight respite in heading. The route leaves Coconut Island and Richardson Reef to port, and then Vin Islet on the same side.

The next segment, at 260° for 10 miles, involves a sharp right-hand turn between Bet Reef to the north and Sue Reef to the south, via Vigilant Channel. It is this narrow passage between two reefs, still marked with a lighthouse each, which was to worry me the most, forcing me to wonder about the infallibility and accuracy of modern electronic navigation, which had thankfully served us well during the preceding hours. To add to my total insomnia during this night passage, the depths are only 10 to 15 meters in this area. The second possible anchorage is downwind of Sue Island, in depths of less than 10 meters, on a coral tongue that overflows from this island to the west. Then 10 miles at 200° to Harvay Rocks to starboard, for the tightest segment of the Strait in relation to the wind: I started the starboard engine as an extra precaution on this course, to make better heading by reducing leeway and maintaining speed. This was the moment, in total darkness, that the block for the second reef chose to explode! An emergency acrobatic maneuver followed, to attach a new block using a headlamp and re-reeve the reefing line again, so as to continue on our route as quickly as possible without drifting dangerously off course.

The final segment of Great North East Channel, at 239° for 17 miles, joins the double isles of Twin Island to starboard. The channel then squeezes between Twin Island and East Strait Island, with depths of 15 to 20 meters, and continues a further 5 miles on 258° to where it joins the Great South East Channel, which stretches from the Great Barrier Reef. At around 0600, we passed the longitude of Cape York, 142 °32' East.

Almost 456 days after entering the Pacific Ocean at Balboa, at the exit of the Panama Canal, we leave behind this huge body of water that will leave us with so many unforgettable memories. Fifteen months have passed, and now we are entering the Indian Ocean. A pair of green and red buoys, which I discovered in the pale light of dawn, a mug of coffee in hand, mark the beginning of Prince of Wales Channel, 14 miles long in 4 segments oriented on an average of 256°. This channel goes to the immediate north of Wednesday, Hammond and the famous Thursday Island. A no man's land for Customs: a special regulatory area where some sailboats choose to complete their entry formalities into Australia, before, in general, continuing their journey on to Darwin. For our part, we considered that spending a few days in the big northern city would not teach us much about Australia, a country so big that we’d prefer to explore one day, maybe, by land.

A new day dawned. Tired from a sleepless night spent in front of the screens at my chart table, but also from sail trimming and even repairs, I watched the dry coasts of the Australian Northern Territories scroll by. Not a living soul to be seen. The current takes us at a speed of 10 knots towards the exit of the Strait. I finally see the Harrison Rock buoy, just visible in the current: the end of our troubles. There are still a few shoals to clear, then we pass close to Booby Island, before sailing again in open water to Kupang, our port of entry to Indonesia, some 1,100 miles away...

With an immensely blue sky, the blue-green waters sparkle. We are now clear of the Pacific! We are in the Indian Ocean. The wind is behind at 15 to 20 knots, and we run under spinnaker, fishing for tuna, and drink ti-punch (made with Papuan rum!) at sunset.

First the Arafura Sea, now the Timor Sea. Our first week in the Indian Ocean will remain in our memory as one of the most enjoyable since our departure from France. Uninterrupted good weather, sailing downwind with a breeze of about fifteen knots and a beautiful sea. I had charted a course slightly north of the direct route to avoid some offshore oilfields, and our only encounters, at the end of the route, were with Timor fishermen on the offshore banks. The new and characteristic silhouette of their boats, on the deck of which I could see through the binoculars, dark-skinned sailors and turbaned heads, inevitably made me think of the pirate ships of the Celebes Sea (not far to the north ), and the stories I loved to read in my youth. For the time being, I didn’t hesitate, as soon as I saw their working lights , to sail in the dark with all our lights extinguished, and at worst, with only our flashing masthead light on: an always intriguing light when you come across it at night, but one which does not necessarily indicate the type of our boat nor our aspect. I also didn’t hesitate to alter course to these boats we encountered by a greater distance. But in all probability these fishermen would have been perfectly peaceful. We only needed our minds and imaginations to get used to Asia, a new playground...

What readers think

Post a comment

No comments to show.