Issue #: 189

Published: May / June 2023

- Price per issue - digital : 7.90€Digital magazine

- Price per issue - print : 12.90€Print magazine

- Access to Multihulls World digital archives Digital archives

For three years now, a group of orcas has been damaging the rudders of small boats off the Strait of Gibraltar, Portugal and as far as the Bay of Biscay. This is unusual behavior for these marine mammals and obviously poses a problem for sailors and fishermen. For the time being, these interactions have been restricted to one region, but the area concerned is located on two of the main blue water cruising routes - the descent to the Atlantic islands from northern Europe and the Atlantic-Mediterranean. In order to try to understand the motivations of these delphinids, also called killer whales, we have gathered together information about the different incidents, and interviewed the scientists. Thanks to their advice, it is possible to significantly reduce the risk of (nasty) encounters. And if such encounters should occur, it is also possible to adopt an attitude that tries to safeguard both these animals and our multihulls and their crews.

In January, a catamaran crossing the Strait of Gibraltar was approached by a group of killer whales. The animals, in what has become their usual modus operandi, quickly attacked the rudders after a period of observation. Half an hour or so later and after many shocks, both rudders finally gave way under the impact and bites that had been inflicted. The crew, who were filming from their boat, even saw the killer whales playing with the rudders that they had just torn off. The multihull was able to reach Morocco under motor. Earlier, in November, a monohull off the coast of Portugal suffered a broken rudder blade and damage to the stern. The boat sank due to a large ingress of water. The crew managed to get into the life raft without too much difficulty, as the killer whales moved away as soon as the rudder became detached. Another ship in the area quickly provided assistance.

Baffled Scientists

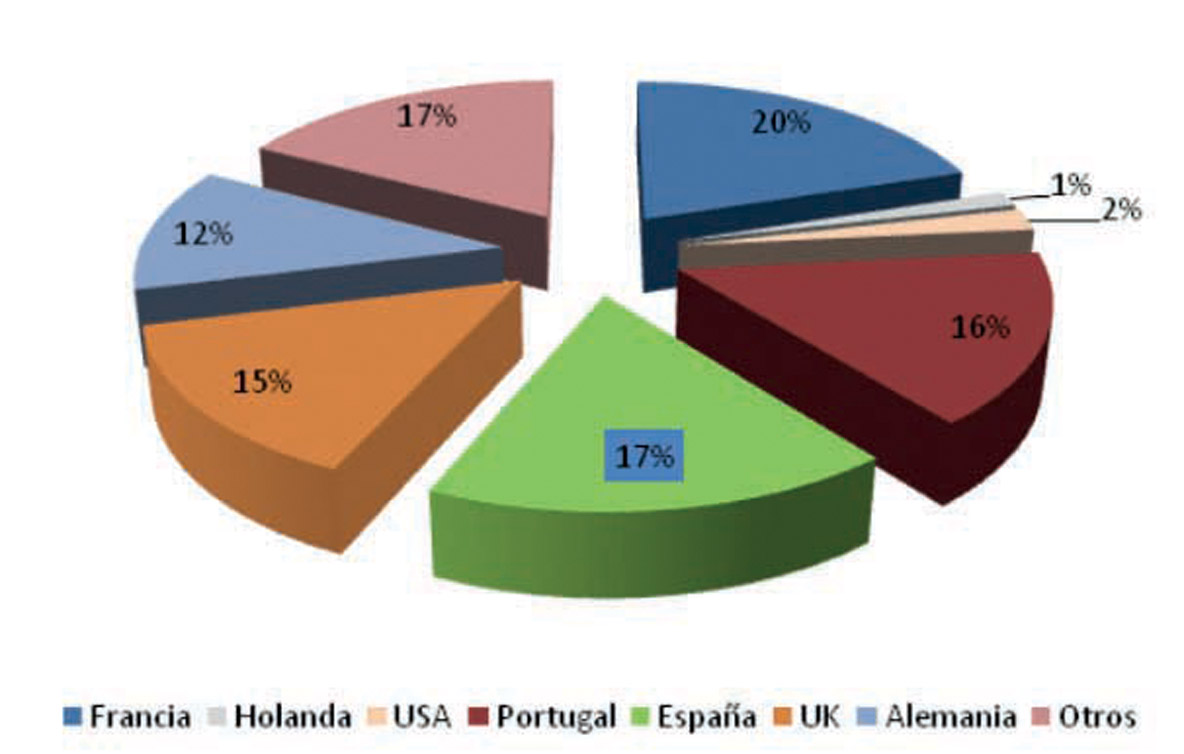

These two recent examples are reminiscent of dozens of other incidents and observations. For the past three years, off the coasts of Spain, Portugal and even France, killer whales have been taking an interest in the rudders of boats that are less than 80 feet (25 m) long and sometimes even attacking them or biting and tearing them off. At first, this behavior left scientists perplexed. But perhaps we should look back at the first reports to get some perspective. This disruptive behavior was first observed just after the European lockdowns and sailing bans, when some juveniles started to interact mainly with monohull yachts. there were also a few cases with fishing boats, RIBs and catamarans. Obviously, this timing raised questions: was the return of the boats to sea the trigger for this new behavior?

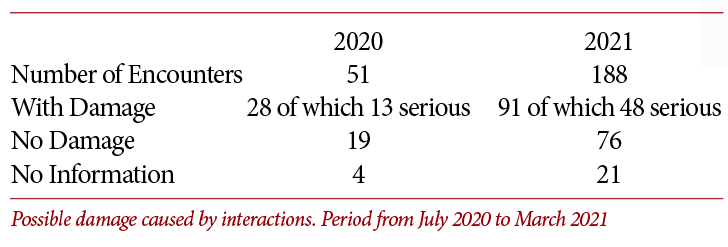

As a result, the orcas bumped, pushed, and even pivoted the boats, which in some cases resulted in damage to the rudders. During the summer of 2020, more and more encounters were reported. In September, Spanish authorities made the decision to ban sailing vessels under 50 feet from the waters of a zone stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar to northwestern Spain (Galicia), including the Portuguese coastline. Fortunately, this situation did not last. To better understand the behavior of killer whales, the Spanish Ministry of the Environment has launched a study of the incidents: «The objective is to provide a detailed follow-up of the cases of interaction between killer whales and sailboats in order to minimize the impact on the species and to ensure the safety of the boats,» said the Ministry in a statement announcing the study in October. In addition, a pilot project is being launched to try to understand the causes and to reduce the episodes of interaction between orcas and sailboats. Around fifty events were recorded in 2020, rising to one hundred and eighty in 2021 and the same number in 2022, underlining the persistence of this unprecedented behavior over time. This long-term situation confirms the need for specific actions based on international coordination between administrations, sailors and scientists to avoid any future damage to people, killer whales and boats. It is for this purpose that the Atlantic Orca Working Group was created. The objective of the AOWG is to ensure the conservation and management of an endangered sub-population of killer whales (see inset: Killer whales in the Strait of Gibraltar) between the northern Iberian Peninsula and the Strait of Gibraltar. It has set up a website www.orcaiberica.org to facilitate the collection and exchange of information between the various stakeholders and to inform sea users (sailors and fishermen) in real time. The AOWG also provides behavioral advice to help sailors to better manage these encounters.

The victims themselves were the first to report on social media and in the press what they perceived as an attack. We can easily under- stand the feeling of these sailors, frightened by animals that can measure more than 30 feet (8 meters) and weigh 8 tons. Obviously, during these accounts, the financial consequences of the damage caused were brought up. Scientists, researchers and administrators quickly became interested in the issue. Ruth Esteban - a doctoral researcher in marine science, working at the Madeira Whale Museum and member of the European Cetacean Society - said that the best thing that specialists could do at this moment is to help minimize the damage to people and boats, by giving advice to sailors on how to react when they find themselves in these situations (see Safety Check panel). Ruth also clarified, based on initial reports, that these interactions were limited to a group of animals living in the vicinity of the Strait of Gibraltar (no other cases have been recorded anywhere in the world). These killer whales travel along the Spanish and Portuguese coasts and as far as Brittany to follow the prey they hunt. This endangered sub-population is highly dependent for its own subsistence on an equally endangered species, the Atlantic bluefin tuna. Killer whales are observed either chasing tuna until the fish are exhausted, or seizing tuna caught by longline fishing boats directly from the lines. This is daring behavior, that could be caused by the depletion of the resource. The AOWG is trying to determine if the family of orcas that interests us, called the Gladis group, is suffering from a lack of tuna and is therefore looking for other means of feeding itself. This is why the hypotheses concerning the motivations of the killer whales first favored a survival signal aimed at those responsible for the depopulation of the tuna. This interpretation is not as far-fetched as it seems. Killer whales have a particularly developed brain and their intelligence is roughly equivalent to that of chimpanzees. The fact remains that the majority of the boats concerned are sailing boats and not fishermen. Some people also think that this is revenge for the use of foils on our most recent racing yachts which sometimes hit cetaceans at (very) high speed. But this phenomenon is very localized and involves young and immature orcas, which would not be able to take revenge for something that they had not experienced.

Ruth Esteban explained that, based on the first photographic evidence, it would appear that at least one adult is present during the interactions with the boats. It was a female. Is she teaching the younger ones? Again, this is not clear. It is also possible that what could be called an attack was not an act of aggression after all. Giant mammals are playful creatures; some scientists believe they approach boats out of curiosity or play. For Ruth,“the word ‘attack’ is too strong, and without proof, it could be that these orcas are just having fun. Eric Demay, a cetologist based in Brittany and founder of the TURSIOPS group for the study and protection of dolphins and cetaceans, is of the same opinion: “I don’t think these are real attacks because if the killer whales had really wanted to attack these boats in order to destroy them, they would have had no trouble doing so! There are examples where killer whales have completely destroyed a boat, even if it meant injuring themselves by leaping onto it. In the current encounters, the orcas do not show any real aggressiveness” , according to this specialist. In his opinion, “It’s just a matter of trying to frighten away the sailboats or to intimidate them, in an attempt to protect their offspring. However, it is often young orcas and at any time of year that take part. These interactions could therefore be training linked to the teaching of hunting or simply a game, without seeking to harm humans”. This behavior is still surprising, as the killer whale is considered a sociable and curious animal, and not particularly dangerous for humans. In the absence of evidence of real aggressiveness, the term «interaction» has been retained to characterize their behavior. Moreover, many of the sailors concerned did not notice any aggressive actions. However, the simple underwater play of an animal weighing several tons can soon lead to significant damage to a boat and even endanger its occupants.

Initially, maritime authorities recommended that in the event of an orca encounter, the engine should be turned off and the rudder immobilized, thus discouraging the mammals from interacting with the submerged mobile structures. This advice proved to be good but not necessarily sufficient: the power of the killer whale is such that no rudder system can resist if it gets too close... The protocol has since evolved: it is now recommended to leave the rudder free of any human or mechanical hold. Another option is slow reverse. But the observation remains more or less the same: in the event of «contact», the rudder stocks are bent, or at best the mechanisms are distorted. Faced with potentially serious damage, some sailors determined to defend their boat went so far as to use a firearm: one orca was found with a bullet in her head. Deafened, she was unable to survive. Such retaliation represents a huge risk if the group of orcas were to attack the boat for real...

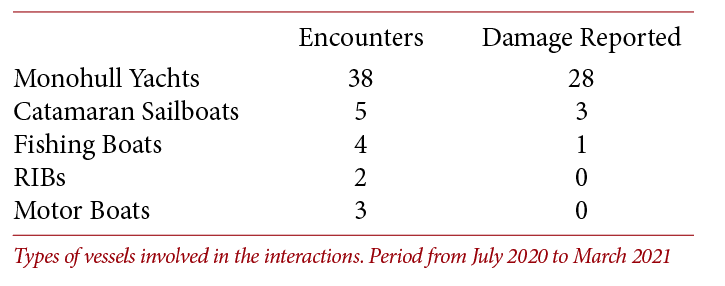

As early as July 2020, the AOWG began a study by collecting all available information on these events and on the habits of the cetaceans in order to prepare a clear response. A precise questionnaire was filled out by the skippers involved. A first report covered all the events recorded up until March 2021, and a few months later, the first bases for a scientific study were presented during a webinar. It was reported that all vessels from 20 to feet (6 to 25 meters) were affected - the average was just over 40 feet (12 meters). Vessels made of wood, composite, steel or aluminum are equally attractive to killer whales. The color of the antifouling is no more important than the fact that one, two or three hulls are submerged. The same goes for the speed of the boat: whether it’s zero or more than 10 knots, it doesn’t seem to make any difference. The same can be said for the sea conditions. It should be noted that killer whales can swim at more than 25 knots; a racing boat, whose appendages were filmed by a camera in order to spot any algae, had its rudders «nibbled» live... There was also the case of a powerful RIB that was harassed by two killer whales at full speed.

During this first time period, we can see that sailboats accounted for the vast majority of the boats that had an encounter with the whales. More than half of these boats ended up with some damage. Motorboats and RIBs fared better, probably because their rudders were smaller or even non-existent. This breakdown simply corresponds to the proportion of the different types of boats sailing on the waters frequented by the Gladis Group of orcas.

Of the total number of incidents, serious damage (torn rudder or the boat needing to be towed away) accounted for a quarter. Minor damage (without significant material damage) accounted for about half of the total number of incidents. Paula Mendez- Fernandeza, one of the AOWG researchers, believes that this is because «when orcas do not find resistance, they can quickly get bored and move away». We do not have the details of the interactions in 2022, but according to the sources that helped us build this survey, there were as many as in 2021, which would tend to suggest that the number of incidents has stabilized at around 180 per year. Another particularly interesting piece of information comes from the last Mini-transat race. For their first leg, the 90 competitors set off from Les Sables d’Olonne (France) to Santa Cruz de la Palma (Canary Islands) on September 27, 2021, and crossed, off the coast of A Coruña (Spain), a zone that at that time was inhabited by the orcas that we are interested in. Four competitors were intercepted but only one boat sustained a level of damage that forced it to put in for repairs. Roughly 1% of the fleet suffered significant damage - an order of magnitude that we will try to substantiate and validate a little more. To find out the real impact on all the boats sailing in this area, we asked Jimmy Cornell who, every five years, records the movements of pleasure boats around the world and publishes his results in his books, such as the latest one - 200,000 Miles - A Life of Adventure. Jimmy uses crossing points such as canals, straits and other obligatory stops to record traffic. He points out that there are no such official statistics, so he surveys the port authorities to produce his figures. The author estimates that the total number of leisure craft passing through western Spain and Portugal - most often to or from Madeira, the Azores or the Canary Islands - amounts to 1,500 per year (of which 1,200 are on an Atlantic circuit). Through his research, Jimmy has established the outbound and inbound traffic in the Mediterranean at between 1,000 and 1,500 vessels. To this we can add between 600 and 1,100 Portuguese and Spanish vessels, including the fishing vessels that have been identified by the AOWG as being able to sail in coastal waters. We therefore have a likely traffic of about 3,600 vessels that sail each year in the area covered by the Gladis Group. With a little less than 180 vessels approached, we can see that there is a 5% interaction on the whole traffic, with serious damage affecting less than 1% of the total fleet. Shipwrecks represent only 0.03% of the total, as there were only two, one in 2021 and one in 2022. During the same period, there were also two orca victims. These figures put into perspective the significant media hype, which has been exaggerated by the term «attack», suggesting a greater frequency and severity of these interactions than is actually the case. But going back to the people involved, it is still too serious a problem to not look for solutions... This is what the AOWG has been doing by recommending actions that have brought some level of security but still do not represent a permanent solution. Statistics have shown that boats respecting the safety protocol - stopping and free steering - are as much affected as those continuing to sail. On the other hand, they are less likely (10% less) to suffer serious damage.

In order to better understand the behavior of these orcas and why they are so attracted to boat rudders, we met with Isabelle Brasseur, a specialist in delphinid behavior. “At the beginning, it is most likely that a young killer whale was attracted by a moving part like the rudder,” she says. “As soon as that experience proved to be positive and satisfaction is obtained, the animal is tempted to repeat it and to share it with the other members of the group and, if there is a common adhesion, to increase the frequency of these experiences. Delphinids have very strong cognitive skills. They show imitation, creativity and transmission abilities. They are able to learn but also to unlearn. Thus, a few years ago, a particular population of orcas had got into the habit of placing the sea lions that had been killed on their snouts. This «fashion» then disappeared. Approaches to boats were reported in the 1970s but this behavior did not continue. Training young orcas is paramount and females may choose not to discourage their young if they feel it is beneficial and useful for group cohesion. The trophy of a hunt is systematically shared, so why not a piece of rudder? Isabelle insists on the necessity to report everything that happens in relation with the orcas. All this information is useful for the scientists to build a common action plan. Consistency of response and linearity of implementation is of utmost importance as orcas can react in contradictory and unexpected ways. For example, the use of pingers (acoustic repellents) that emit unpleasant frequencies can have a negative result - in addition to the noise pollution suffered and the risk of pushing the orcas out of the areas where they still manage to feed, cetaceans can become accustomed to the boat’s signature and even be attracted to this transmitter! Similarly, it is better not to leave your dinghy behind the boat, as orcas have been known to turn them over for fun. «Adopting the most neutral behavior possible in order not to offer satisfaction to the orcas is the safest way to avoid any dissemination of new habits,” concludes Isabelle.

So what else can we do? In the event of an encounter, our chances of getting away with-out any material damage are still one in two... The simplest reasoning would be to increase the proportion of the 95% of navigators who did not have an encounter by developing a strategy to avoid the area where the orcas are at that particular moment. To do this, we would have to communicate as effectively as the members of the Gladis group... The Facebook account “Orca Attack Reports”, with 26,000 members, has dedicated its pages to communication on this topic. The AOWG, again, records the position and date of the interactions. The analysis of these sightings has provided valuable information on the movement of killer whales and their typology. Of the 50 orcas recorded between Gibraltar and Galicia, only 14, forming one or two clans, seem to be involved in the interactions with the boats. Scientists have identified them - which is why it is important to photograph them and give their position - and they have given them each a name. The individuals of the Gladis group are thus followed according to the observations and the information received. On the AOWG website, a map of potential interaction is updated periodically. The reappearance of killer whales in the Strait of Gibraltar in January had been reported. There is also a question of seasonality that one should be aware of before sailing in the Spain/Portugal region, as killer whales follow their prey, which also move. As mentioned above, the Gladis killer whales love bluefin tuna, which reproduce in the Mediterranean during the winter before heading back to the Atlantic. The orcas wait for them near Gibraltar and then in the Gulf of Cadiz from January to June. Then, as the waters warm up, the tuna swim up the coasts of Portugal and Spain in June and July and even this summer to the Bay of Biscay. Killer whales follow their “larder” and tend to stay off A Coruña and Portugal until autumn. They then move further offshore and do not return to the Strait until the beginning of the following year. Laurent Marion of the “Escale Formation Technique” school, which is one of the top training centers for cruising yachties, does not hesitate in recommending that sailors adapt their route by sailing along the Moroccan coast in winter or avoiding A Coruña at the end of the summer. The other solution when sailing down to the Canary Islands from the Mediterranean is to set sail in autumn or to sail well offshore to avoid the most problematic areas if you are travelling from northern Europe. Radio alerts on VHF channel 16 have been set up to signal the presence of killer whales. The AOWG is collaborating with the Friendship-Orcas project. CEMMA will allow, among other things, boaters to benefit as soon as possible from the advances made by scientists. Over the course of this spring, a new web platform will be operational, and a test mobile application will be launched. The scientists don’t think that the killer whales’ actions will suddenly and miraculously stop. A habit has been established and the goal is to prevent the phenomenon from spreading. All the work done by the AOWG is crucial for the future and it is important to follow, in a coordinated way, the organization’s recommendations.

The orca - or killer whale - is a species of marine mammal of the sub-order of toothed cetaceans, the odontocetes, and more precisely of the delphinidae family of which it is the largest member. It inhabits areas stretching from the Arctic and Antarctic to the tropics. Its diet is very diversified, although populations often specialize in particular types of prey. Some feed on fish, while others hunt marine mammals including large whales (usually calves). Killer whales are considered super predators, and their name actually refers to the fact that they are whale killers. Killer whales are particularly sociable, with some populations consisting of several matrilineal families that are among the most stable of all animal species. Sophisticated hunting techniques and vocal behaviors, which are often specific to a particular group and which are passed down through generations, have been described by scientists as cultural traits. The life expectancy of an orca is estimated to be over fifty years and females give birth to five or six pups during their lifetime, three-quarters of which do not reach maturity. There are several ecotypes of orcas, which can be considered as subspecies or even different species. The nomadic, constantly moving and silent orcas consume almost exclusively marine mammals. The deep-sea orcas feed mainly on sharks and live in groups.

Finally, the resident killer whales that live in coastal waters feed mostly on fish. They live in groups of five to fifty individuals and communicate constantly with a varied and rich repertoire. They frequently use echolocation which consists of emitting small sounds similar to clicks and then listening to their echoes, which allows them to detect prey and find their way in turbid waters. They are therefore particularly sensitive to noise pollution. The conservation status of killer whales according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is «data deficient», meaning that there is not enough data regarding the global population of killer whales to know if this species is endangered. For Isabelle Brasseur there is no doubt that some local sub-populations are threatened or even already endangered... notably because of the disappearance or disturbance of their habitat, pollution, or lack of food. This is the case of the Strait of Gibraltar killer whales, which are considered (based on studies of photo-identification data, mitochondrial DNA, microsatellite genetic markers, stable isotope ratios and contaminant loads) to be distinct from other sub- populations in the Northeast Atlantic. This group of about 50 individuals consists of five family clans, with a low number of mature individuals. This population feeds on bluefin tuna. The annual nutrition requirement is about 14 tons for the largest and 4 or 5 for the smallest. Although adult survival rates have been estimated to be sustaining stable population levels, low long-term turnover suggests a near future decline - unless conditions improve. For these reasons, this subpopulation of killer whales was catalogued as vulnerable by the Spanish Ministry of the Environment in 2011, which subsequently published a conservation plan in 2017. It has since been assessed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List in 2019.

■ Stop the boat (stow the sails), turn off the autopilot, leave the helm loose (if sea conditions and location allow)

■ Contact the authorities (telephone 112 or VHF channel 16)

■ Keep your hands off the helm and stay clear of any part of the boat that could fall or turn suddenly.

■ Do not: physically confront the orca, yell, throw objects, or try to touch it with anything

■ If you have a camera or smartphone, try to take pictures, especially of the dorsal fins - it will help with identification later. Contact email: gt.orcas.ibericas@gmail.com

■ Only make sure the rudder turns and still works AFTER the blows or shocks have stopped

■ In the event of damage, request a tow.

This protocol lists the first pieces of advice to follow in the event of an interaction. To this can be added other new techniques that are proving effective:

■ In light airs, go astern very slowly (2-3 knots)

■ Portuguese boaters use a long metal bar that they dip partially into the water; from the deck, they hit this bar with a hammer, probably emitting vibrations or frequencies that repel the animals.

What readers think

Post a comment

No comments to show.